Many consumers and even professionals will occasionally utilize the term “freeze-dried” or “freeze dehydrated” interchangeably, but the actual situation is more complex. While both methods seek to remove water from food (or other perishable items) in order to extend the shelf life of the product and facilitate transportation or storage, the methods are fundamentally different. This article discusses the definitions of “freeze-dried” and “dehydrated”, their respective processes, the differences between these processes, the implications of dehydration and freeze-drying on nutrition, shelf life, texture, rehydration, cost, and ideal uses, and when to choose one over the other. Understanding these discrepancies is crucial to businesses (food producers, outdoor suppliers of food, emergency providers), developers of products, and consumers.

Definitions and How the Two Methods Work

- What Is “Dehydration”

Dehydration is perhaps one of the most oldest methods of preserving food. At its most basic, it’s the removal of moisture from food by applying heat (or air plus a mild heat) over a period of time, such as the sun’s dry light, the air’s dry air, or the use of modern electric food dehydrators.

During periods of dehydration, warm air (or controlled low-to mid-range heat) moves around the food, which causes water to evaporate in a gradual manner.

The removal of moisture is significant, but not entirely complete: typically, foods that are dehydrated have a residual amount of water, and dehydration reduces the overall water content of the food, which is typically around 70-95 % of the initial moisture. This is dependent on the method and the food type.

The outcome: food is lighter, more stable on the shelf than fresh, and has a lower propensity to be microbially spoiled. This is useful for snack items, dried fruit, jerky, herbs, etc.

Because dehydration is dependent on temperature, it can affect the flavor, consistency, and content (particularly sensitive to temperature), and it can lead to shrinking or structural changes in the food.

- What Is “Freeze-Drying” (Lyophilization / Freeze Dehydration)

“Freeze-drying” is also known as lyophilization (or in other contexts, “freeze dehydration”). It’s an enhanced, modern method of storage. Instead of simply waiting for the ice to dry out, freeze-drying involves a two-step process: first freezing the product, then removing the water from the ice by means of a low-pressure (vac) transition. This means that the ice directly transitions from solid to vapor, avoiding the liquid phase.

Main steps:

Freeze the product to a great degree, typically at a low temperature (as determined by the product).

In the absence of air, increase the temperature slowly to cause the ice to sublimate, and the water will pass from being solid to vapor without melting.

Ultimately, this results in a product that is dried and has lost most of its moisture, typically 98-99% of water content.

The product is then sealed (often with oxygen absorbers or barrier packaging), which prevents moisture or oxygen from entering, and this preserves the shelf life of the product.

Because of the lack of heat in the process of freeze-drying, the method avoids the liquid phase of water and thus preserves the structure, flavor, color, nutritional value, and potential to rehydrate the original object.

Why They Are Not the Same — Key Differences & Implications

Despite being covered by the same umbrella term, dry food and preserved food (or other materials) have different characteristics in multiple areas. Here are the significant differences and their implications for food professionals, food suppliers, or meal providers.

- The effectiveness of moisture removal and shelf life are both considered.

Moisture removal: Dehydration typically removes 70-95 % of moisture; freeze-drying can remove up to 98-95 %.

Life on the shelf: Because items that are freeze-dried have almost all of their water removed, this leaves them with a longer shelf life. Some sources claim that properly stored freeze-dried foods can last for up to 25 years in optimal conditions.

Conversely, dehydrated items have a shorter shelf life, which is typically months to a few years, depending on the storage conditions, residual moisture, and packaging.

Implication: For long-term storage (emergency food procurement, military supply, space travel, long-haul transportation), the freeze-drying process is beneficial. For short-term meals or smaller storage requirements, dehydration is sufficient.

- Nutritional retention, flavor, color, texture, and rehydration quality.

Because of the avoidance of heat damage and the direct conversion of ice to vapor, freeze-drying is more beneficial to the preservation of heat-sensitive nutrients (such as vitamins, enzymes, flavor compounds, color pigments, and the original structure).

Freeze-dried goods typically have a retention rate of around 95-97% of vitamins, minerals, and overall nutritional value compared to the fresh counterpart.

The flavor and texture of freeze-dried food are often light, airy, and porous, which produces a crispy or crunchy feel when dry; when water is added (rehydration), they can often regrow their original shape, texture, and flavor, making them similar to fresh food.

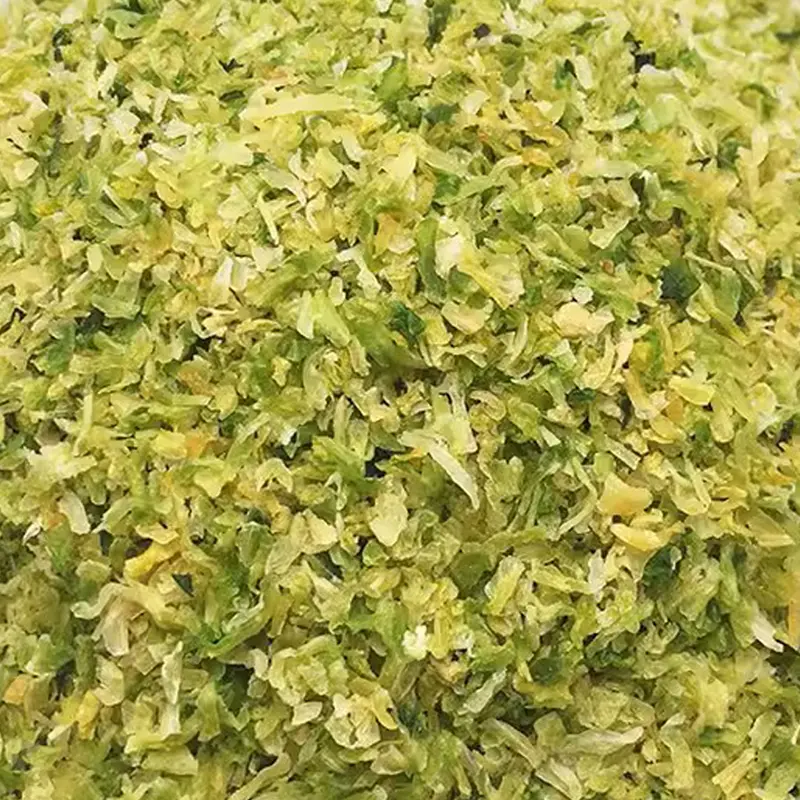

For food that is dehydrated, because heat and airflow cause the moisture to evaporate, the texture is typically more chewy, dense, or leathery (particularly with meats), or shrunken/shriveled (e.g., dried fruits).

The flavor and aroma of dried food may be altered — some chemical compounds that are volatile (flavor, aromatic oils, vitamins) are destroyed during the process of heat drying.

Implication: If the quality of the product (taste, nutritional value, consistency of rehydration) is of paramount importance, such as in premium food, pre-packaged food, or high-end dried produce, then freeze-drying is superior. For smaller snacks, jerky, or less-sensitive ingredients, dehydration is sufficient, especially when budget concerns are involved.

- The speed and ease of rehydration.

Because the freeze-dried items have had their water extracted via the sublimation process and have a porous, “honeycomb-like” internal structure, they quickly and completely rehydrate. Many foods that are freeze-dried can be rehydrated with cold or warm water in just a few minutes, often receiving a near-fresh state.

Conversely, foods that are dehydrated have a higher water content and are often compacted; this may slow the process of rehydration down to a point that requires heat or a longer soak time, and may not regain the original shape or texture.

Implication: For emergency shelters, food from campgrounds, instant soups, or situations that require rapid retribution, freeze-dried goods are beneficial. For long-term food items or snacks that are eaten dry, dehydration is sufficient.

- Device, Price, and Energy Expenditure

The technological and equipment requirements for freeze-drying are significantly greater than for dehydration.

Supplies: Freeze dryers (commercial or domestic) necessitate vacuums, refrigeration, and control of the pressure cycle; these features are more intricate and expensive.

Energy expenditure: The process of freeze-drying takes longer (gradual sublimation, secondary drying, or freezing) and is more energy-intensive than other simple dehydration methods or air-drying.

Price: These factors contribute to the cost of freeze-dried food production, which in turn increases the price of the product in the stores.

Dehydration is, however, more complex, more expensive, and typically accomplished with basic equipment (such as sun-drying, ovens, low-cost dehydrators), lower energy costs, and shorter processing times.

Implication: For large-scale, high-end, long-term storage food production (e.g., emergency food, expedition food, space/military supplies), the initial cost of freeze-drying is often justified. For cheaper snacks, such as jerky, or home storage, dehydration is still commonly employed and is economically viable.

- Product Adequacy & Use Cases

Because of their different properties, foods that are freeze-dried and dehydrated are appropriate for different purposes.

Freeze-dried: best for emergency food supplies, backpacking food, military or space eating, instant soups/meals, high-value produce (berries, vegetables, meats), or rehydratable (sweet potato s, pumpkins, broccoli, etc.

Dehydrated: beneficial for snacks (dried fruit, jerky), low-cost stable food products, homemade dehydration (fruits, herbs), budget-friendly pre-prepared food, or instances where the texture (chewy) is acceptable or preferred.

Why Many People Conflate “Freeze-Dried” and “Dehydrated” — And Why That’s Misleading

Since both freeze-drying and dehydration lead to “dry” foods that are lightweight, long-lasting, it’s reasonable to consider them together or as being the same. Some sources define freeze-dried food as being dehydrated.

However, this association can misrepresent important differences. For business owners, manufacturers, or developers, understanding the difference can lead to a poor understanding of the product’s position, insufficient packaging or advertising, or consumer dissatisfaction if the expectations are misaligned (e.g., expecting a long shelf life or quick rehydration, but using common dehydrated goods).

The cause of the confusion is often attributed to terminology: because both processes involve the removal of moisture, the general term of “drying” or “hydration removal” is applied to both processes. Some marketing or supply-chain documents may utilize terms like “freeze dehydration” ambiguously. However, technically speaking, freeze-drying is different from conventional dehydration.

“Freeze Dehydrated” — When the Term Is Used, What Does It Actually Mean?

Given the ambiguity in the name, you may encounter terms like “freeze dehydrated” or “freeze-dehydrated” in marketing or supply contexts. This is especially true of the term in marketing. What does it suggest? Typically, when a product is referred to as “freeze-dehydrated”, it attempts to communicate that freeze-dehydration (lyophilization) was employed instead of conventional heat-based dehydration. Other words, “freeze-dehydrated” means “freeze-dried,” not the standard way to dehydrate.

In industry talk, the term “freeze dehydration” may be employed to attract consumers or buyers who are familiar with the more general term “dehydrated”, while also indicating a more expensive method of preservation. Because the process of freeze-drying produces a dry product that is similar to conventional dehydration, but with a superior quality, the term hybrid is intended to combine familiarity with precision.

Key takeaway for professionals that see “freeze-dehydrated”: If you see the term “freeze-dehydrated”, make sure it’s referring to a true lyophilized product, or confirm the process (freezing + vacuum evaporation). Don’t assume it’s dehydrated by default; this implies that it’s frozen.

Pros — Freeze-Drying vs Dehydration (From Industry & Commercial Perspective)

Summarizing the benefits and drawbacks of each method, especially in regard to an industry, supply chain, or product development, is beneficial.

- Benefits of Freeze-Drying (Freeze Dehydrated)

Extremely effective moisture removal, which is up to 98-99%, maximizes the shelf life.

Excellent conservation of nutrients, flavor, aroma, color, and structure – minimal heat damage preserves heat-sensitive vitamins, aromatic compounds, textures, and structures.

Immediately, full rehydration – the porous structure allows for quick water absorption; this often restores the texture and flavor of the water very close to the original state.

Extremely long shelf life if stored properly – this is ideal for emergency food, long-term storage, and supply chain stability.

Lightweight and compact – minimal water volume decreases the cost of transport and storage, making products ideal for backpacking, shipping, and disaster relief.

- Conventional Dehydration’s advantages.

Simplicity and low cost — it’s simple to use (sun, air, dehydrators), it’s low cost, and it’s accessible to both small producers and homeowners.

Celebrated products, such as dried fruits, jerky, herbs, and spices, are common in the market; consumers are aware of what to expect.

Lower-cost products that are more budget-friendly; these are ideal for the snack market, the mass market, and budgeted meals.

Flexibility in production — dehydration is effective for many food types (fruits, meats, herbs), the moisture level of the food will be reduced by dehydration, which is more effective for small quantities or individual producers.

Misconceptions and Why “Freeze-Dehydrated = Dehydrated” Is an Oversimplification

Because of the overlap in the end state ( dried, shelf-stable food), many people believe that “freeze-dried” and “dehydrated” are synonymous. However, it’s professionals who are at risk of this combination.

It can cause problems with mislabeled products, which can lead to issues with regulatory or consumer trust.

It can lead to mislabeled packaging or storage — for example, storing desiccating food as if it had a freeze-dried shelf life, which could lead to spoilage.

It can mislead customers by providing them with quick rehydration or a near-fresh product quality from items that are dehydrated.

It can adversely affect a brand’s reputation if the product’s quality does not meet expectations (flavor, nutrition, texture).

As a result, the definition of the word freezing is important: use the term “freeze-dried” or “freeze-dehydrated (freeze-drying process)” when sublimation is employed, reserve the term “dehydrated” for heat/air-drying methods.

Key Criteria to Evaluate When Selecting “Freeze Dehydrated” or Dehydrated Products (For Suppliers, Buyers, Retailers)

If you harvest, produce, or sell dried goods – here’s a list of factors to consider:

Know the method of drying – verify if it is freeze-drying (freeze dehydration) or based on heat.

Check the moisture content residuality — a lower amount of moisture is better (e.g., 1-2%) because it indicates a more efficient freeze-drying process; a higher amount of moisture implies dehydrated or low effectiveness of the drying process.

Evaluate the packaging and sealing — For foods that are freeze-dried, containers that are airtight or barrier-packaged, and possibly possess oxygen absorbers, these are crucial to maintaining a long shelf life.

Think about the storage conditions—dry, cool, dark, and airtight environments have a long shelf life; freeze-dried products are particularly susceptible to moisture or oxygen exposure.

Correspond the product to its intended purpose or the consumer’s desired outcome — is this long-term storage possible? Immediately available?Snacks? Preferred textures and tastes? The price of the product?

Compare the cost of products with their value — freeze-dried products have a higher cost, but they typically provide a higher value (nutrition, shelf life, rehydration). Hydrated products are priced lower, but the quality of the products is sacrificed.

Communicate openly — when marketing or labelling, be specific: “freeze-dried,” “shelf-stable 20 years,” “lightweight backpack food,” or “dehydrated snack,” etc.

Why “Is freeze-dried and dehydrated the same?” Is the Right Question — But the Answer Must Be Qualified

Unconditionally answering the question with either “Yes” or”No” doesn’t address the actuality. The correct response is: No, they aren’t the same, though they share a common goal of moisture removal and preservation.

The procedures (the process of evaporation of heat or freezing, plus the procedure of sublimation of water) are fundamentally different.

The outcomes (moisture content, shelf life, nutrient retention, texture, and rehydration quality) are significantly different.

The expense, equipment, suitability, and practicality of the process also differ.

Understanding these differences – from a technical, economic, and consumer perspective – is crucial to any participant in the food, packaging, supply, or retail chain.

Conclusion — In Which Cases “Freeze Dehydrated” Is Essential, and When Dehydrated Is Enough

If you’re manufacturing or purchasing food for long-term storage, emergency supplies, outdoor meals, pre-packaged meals, or high-nutrient produce, then “freeze-dried” (or “freeze-dehydrated”) is more likely to be the appropriate, often necessary, and more expensive option. The benefits of shelf life, nutritional value, hydration, and quality product often compensate for the cost and equipment needed.

If your objective is simple snacks, low-cost dried fruit, low-volume home dehydration, or products that have a chewy texture and can be stored for a few months to a couple of years, then conventional dehydration is likely sufficient. It’s practical, simple to implement, and generally embraced.

Ultimately, the words freeze-dried and dehydrated are synonymous, but they are different. Using the appropriate term and method of comparison is crucial. For companies, product developers, and retailers: having a clear, transparent, and consistent approach to quality that matches the consumer’s needs will lead to success.